Hello,

We saw several long game bets across public, private, and hybrid asset classes this week.

Starting with Bank of Baroda, which emerged as the top bidder for Jet Airways’ prime BKC office, a reminder that distressed assets still attract aggressive strategic interest. The state-owned lender’s play in a premium Mumbai location reinforces the recent confidence seen in India’s office assets.

Meanwhile, the Wealth Company launched a ₹2,000-crore Bharat Bhoomi (real estate) Fund focussed on Tier II and III cities in India.

Japan’s Mizuho is reportedly looking to acquire Avendus, an Indian investment bank, a move that would underscore both the value of homegrown advisory talent and India’s enduring M&A relevance despite global softness.

I hope you enjoy this week’s roundup, and please do connect with me on LinkedIn to find out how I can help with your next M&A deal.

Let’s dive in.

Deal Tracker

Our weekly roundup of confirmed M&A deals in India.

Market Trends

Hope floats

SEBI’s recent moves to enforce Minimum Public Shareholding (MPS) norms, most notably from its June 18 board meeting mandating 25% public floats, has the potential to reshape India’s capital markets.

The watchdog’s gaze has led to:

- The UltraTech Cement divestment worth ₹667 crore following its 82% stake acquisition in India Cements.

- Adani Offshore Funds’ penalisation for alleged proxy promoter holdings by Mauritius-based funds, violating disclosure rules.

These cases signal an assertive stance on transparency and liquidity, with the regulator pushing markets toward global best practices.

India sadly still does not rank among the countries with the biggest institutional investors globally despite being among the fastest growing economies in the world.

But as liquidity improves, and pricing becomes more transparent, international institutions will participate with greater confidence. SEBI understands that international funds need the ability to buy or sell in volume more than they care for the India story.

Higher float limits the power of ‘promoters’ – i.e. a major shareholder, typically a founding family member, who may not be involved in daily operations but retains significant control – making room for better governance, smoother successions, and board independence.

The renewed pressure on the promoter-held threshold is aiming to open doors to foreign inflows via benchmark indices like MSCI and FTSE.

Sometimes compliance isn’t just about following the rulebook, though.

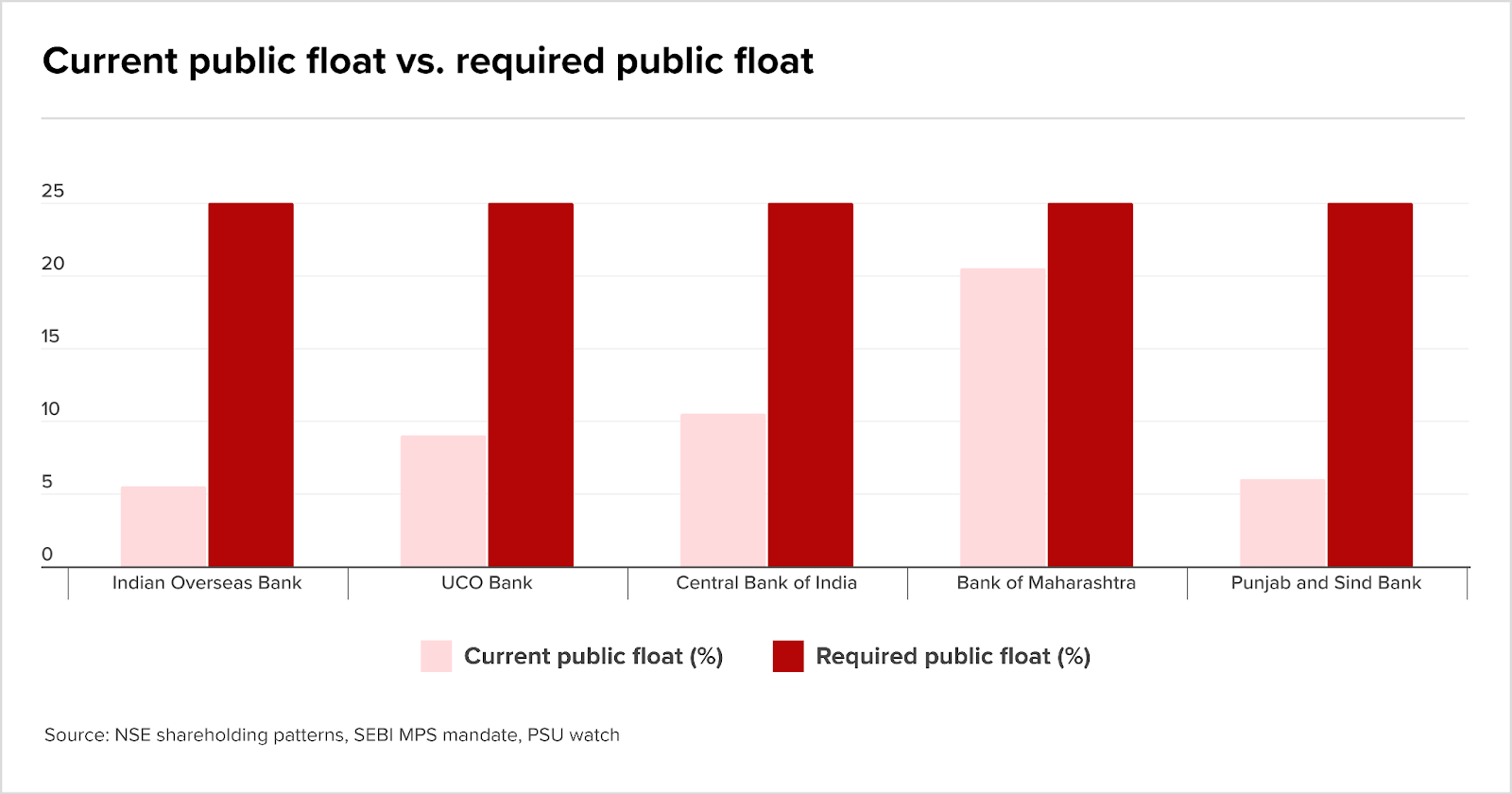

The authorities might want to look in the mirror. Several public sector banks and firms are still over 90% government-owned (under SEBI’s new MPS rules, even government-owned firms must reduce their stake to ensure public liquidity as they move towards privatisation).

SEBI, in a departure from its one-size-fits-all approach, has offered them a voluntary delisting route at a fixed premium without holding the markets hostage.

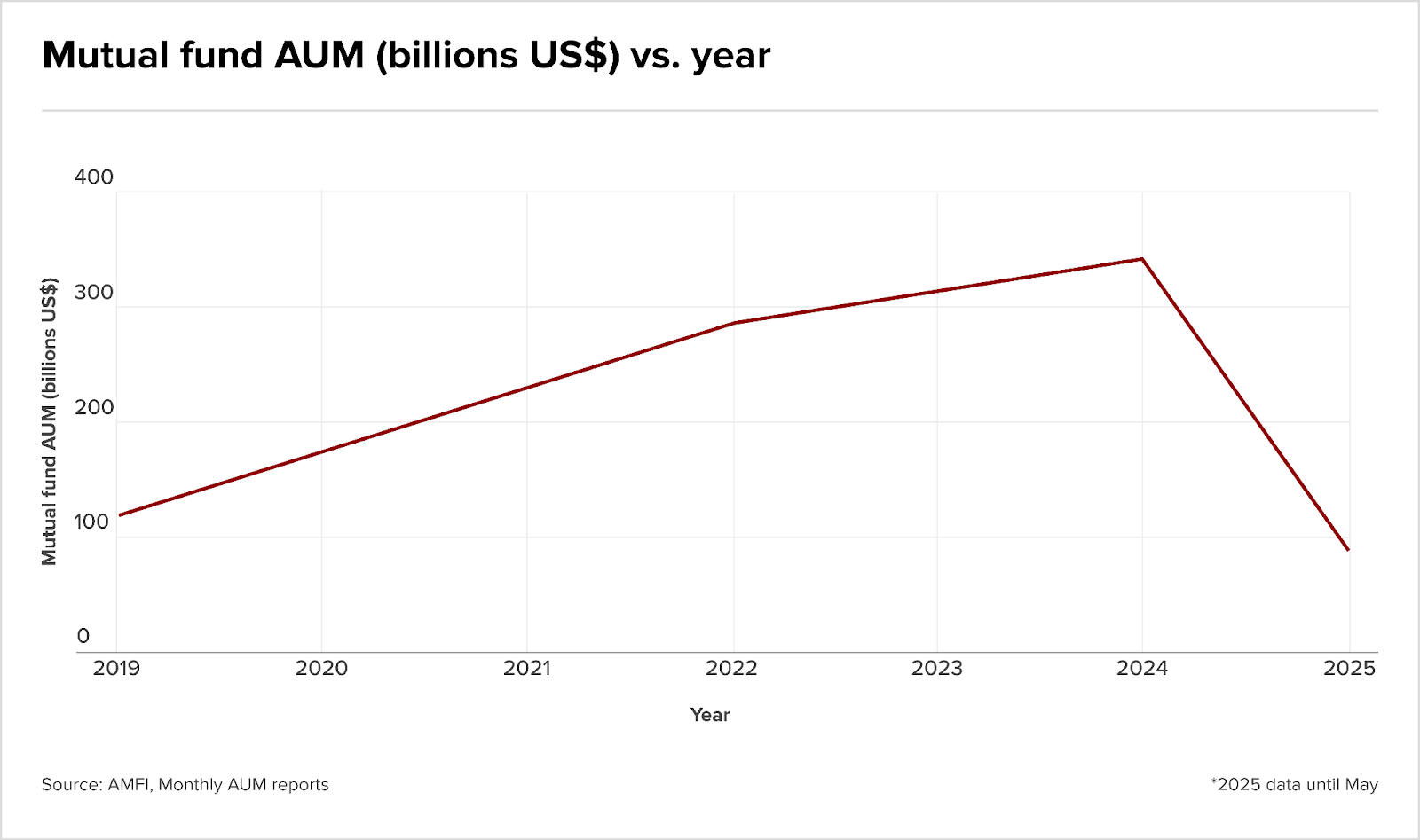

AUM growth

Now let’s look at mutual fund AUM growth since 2019.

With capital swelling, float discipline is a natural next step.

But, oh no, look at the float levels of PSU banks:

How far some of them still need to go.

If corporate governance is a concern, MPS is proving to be a useful anti-corruption tool.

SEBI has cracked down on circular trading, proxy ownership, and board capture; making price rigging less likely.

And who toes the line? Reliance, Aditya Birla Capital, UltraTech, and Yes Bank are moving to comply while UCO, IOB and other public sector banks are lagging.

What about us?

To risk a bad metaphor – float matters but Indian markets remain top-heavy.

TCS, with a 63% free float, doesn’t dominate despite its size, as much of its stock is locked in. Hindustan Zinc, despite being a PSU, has a healthy float at approximately 60%.

Mutual funds investing in India are overweight on liquid large caps. Small and mid caps with low float don’t get the same attention risking concentration.

Why does promoter culture persist? No inheritance tax, for one. Heirs can sit on shares indefinitely equating cash with emotional legacy. SEBI tries to pierce through the corporate veil of control by requiring disclosures even of distant relatives – not done in any developed market. India’s idiosyncratic capitalism is such, it makes this necessary.

But history has stuck to the cap tables. Privately-managed lender ICICI Bank which carries government shareholding from its development banking past. HDFC, by contrast, shows what a clean private float may look like. Different legacies matter in non-family held concerns as well.

Targeting workarounds

But promoters still game the system. Buybacks before stake sales, inflated valuations, proxies, preferential allotments.

SEBI is responding with more rules, more enforcement, more disclosures, and a shift from box-ticking to behavioural scrutiny.

The fuss is not petty housekeeping. For an unequal country like India, this is nation building. As billions of dollars flood into the country it needs capital structures that can absorb them.

The rumour mill

- US firm commits 25cr for IIT-K startups in aerospace, defence

- Operator-founders 3x more likely to raise seed rounds than rest of India’s tech startup ecosystem

- Strategic Investment set to strengthen Kayess Square’s Advanced Taxation Offerings

- IPG begins workforce restructuring in India ahead of merger with Omnicom

- BAT may begin phased stake sale in ITC Hotels: Sources

- IFC pledges $60 million to Motilal Oswal’s new fund targeting India’s mid-market companies

- IndiGo shares plunge 6% as promoter plans $1 billion stake sale

- PNB shares in focus following completion of 21% stake sale in India SME Asset Reconstruction Company

- RCB owner Diageo dismisses stake sale reports, calls them ‘speculative’

- Nykaa Fashion could break even in four years

- Bank of Baroda emerges top bidder for Jet Airways prime BKC Office

- Hemadri Cements to consider voluntary liquidation

- VC Major Foxhog Aligns with IIT Kanpur to Build Defence, Aerospace, Agritech Startup Pipeline

- India Inc Set To Take Big Bets, To Double Capex To USD 850 Bn Over Five Years

- SAM, AZB, HSF, Ashurst act on BAT’s USD1.4bn divestment

- RCB to be sold? Diageo weighs options for stake sale in IPL 2025 winner

- New Joint Venture Plans to Boost India’s Denim Production

- Prologis Announces Joint Venture with Jhaver Group to Expand India Presence

- CLR Facility Services Secures $15M from BII to Boost Inclusive Jobs & ESG in Facility Management

- Mizuho is said to be on cusp of buying Indian investment bank Avendus

- DCM Shriram to acquire Hindusthan Speciality Chemicals for ₹375 crore

- ICRA to acquire risk solution firm Fintellix India for $26 million

- Beyond the buyout: India’s legacy funds must ‘modernise or make way’

- Capital 2B leads funding in Leumas and other Indian deals worth $310m

- Malaysia’s creador in talks to invest in True North-backed Indian NBFC, Infinity Fincorp

- General Atlantic fund admin taps over $500m for SE Asia opportunity

- Novo Holdings eyes expansion in food, agri, and climate tech sectors in India, Indonesia

- Oben Electric raises $5.8m from Helios, and India deals worth $60m

- Single specialty hospitals win over PE investors in India

- HomeEssentials raises $2.2M from India Quotient, plans omnichannel expansion

- India Inc.’s capex poised to touch $850 bn by 2030, signalling corporate India’s bold growth bet amid policy tailwinds: Report

- Case against Supertech, promoters in Rs 126-crore IDBI Bank loan fraud case

- Israeli startup Coralogix to invest bulk of $115 million fundraise in India

- Aditya Birla Capital shares rise nearly 3% to 52-week high despite Advent’s partial stake sale worth ₹568 crore

- IREDA share price jumps over 2% after allotment of 50% equity to LIC in ₹2000 crore fundraise

- Jio Financial Services acquires 7.9 crore shares of Jio Payments Bank from SBI

- Transition: TVS Capital revamps board, eyes tech-driven opportunities

- Apax, Bain, Carlyle in fray for majority stake in Harman India’s digital arm: Report

- As big private hospitals expand away from cities, small players feel the heat in Kerala

- How JSW Group Plans to Fund ₹9,000 Cr Buyout of AkzoNobel India

- Steady Dividends Give Govt Food for Thought on Hindustan Zinc Stake Sale

- IndiGo’s top shareholder denies reports of stake sale

- Family Office Boosts U.S., India Trade

- Private equity investments to revive in India in second half of 2025: Report

- How was Leapfrog’s exit move from India financial services firm

- Is actis making any money by selling Profectus to PE-backed Ugro Capital

- Artha India Ventures to make final close for growth fund as commitments cross Rs 400 Cr

- MS Dhoni-backed Garuda Aerospace boosts Series B round with $1M infusion

- Rare earth magnets crunch, explained; Artha India Ventures’ growth fund

M&A news

- Indian Investment into UK At an All Time High

- Jubilant promoters eye Rs 2,000 crore via stake sales for Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages deal

- Dixon Technologies shares in focus on JV with Signify to strengthen lighting business in India

- ITC shares in focus after Rs 472 crore acquisition of Sresta Natural Bioproducts

- JioBlackRock Investment Advisers gets Sebi nod to start advisory business

- Mukesh Ambani makes multibagger returns by selling Rs 7,700 crore worth of Asian Paints shares

- CCI approves Delhivery’s acquisition of Ecom, M&M-SML Isuzu deal

- Media firm Bertelsmann sells half of startup fund to outside investors

- Jefferies sees promising M&A targets in biotech sector amid stabilizing market

- TPG at Morgan Stanley Conference: Strategic Growth and M&A Insights

- NCLT admits insolvency plea against Gensol Engineering

- NCLT approves Rs 67-crore resolution plan for Trident Sugars

- India’s private equity revival: Growth expected in H2 2025

- Nothing strengthens India strategy with local manufacturing, investment, and expansion plans

- Flush with funds, starved of conviction: Inside the Great Indian startup pause

- What RBI’s 3 surprise moves in its June policy signal about its growth outlook

- India’s Motilal to enter private credit, ropes in modulus head

- Taiwanese electronics giant Foxconn’s India share in global assets hits 11%

- Madhvani Group to invest ₹10,000 crore in India over the next 5 years

- At ₹11 trn, India Inc capex pips govt capex in FY25; will the trend last?

- India’s Deal Activity Slows To 2025 Low In May Amid PE Decline

- Emmer Capital CEO overweight on India, bets on private banks, discretionary & defence

- UK’s BII joins cap table of India’s FlexiLoans in $44m Series C round

- India deal review: Startup funding edges up in May but still below year-ago levels

- Continuation funds in India are a natural progression, not due to exit pressure: Multiples PE

- Reliance trims stake in India’s Asian paints

- Strategic M&A activity remains resilient in India amid broader deal slump

- World Bank lowers global growth forecast to 2.3%, keeps India’s growth rate at 6.3%

- Multibagger Penny Stock Below Rs 50: Company Acquired 69,70,000 equity shares of Pioneer Industries Private Limited

- Vedanta confirms divesting 1.6% stake in Hindustan Zinc for Rs 3,028 cr; announces Rs 7 interim dividend

- In Q1 2025, enterprise SaaS M&A deal count hit 210, according to PitchBook

- JSA Advises Summit Digitel on INR 1,475 Crore Listed NCD Issuance via Private Placement

- Indian Overseas Bank, Punjab & Sind Bank, other PSU bank stocks rally up to 4% on report of accelerated govt stake sale

- Domestic private capital plays a key role in financing Indian mid market businesses

- India’s tech capital Bengaluru jumps 7 spots to rank 14 in Global Startup Index

- Jyothy Labs Sets Investor Meet with Nippon Life India AIF for June 17

- NIIT shares in focus as ICICI Bank sells 18.8% stake in NIIT-IFBI

- Premier Energies block deal: Quant Mutual Fund, Premji Invest, SBI Life among top buyers

- SEBI Rolls Out Settlement Scheme For NSEL Stockbrokers

- Gaming start-up MetaShot raises Rs 2 crore from Karnataka government’s venture fund

- CCI approves the proposed combination involving acquisition of SML Isuzu Limited by Mahindra and Mahindra Limited

- Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group and SBI launch wealth management JV

- NSE International Exchange signs MoU with Cyprus Stock Exchange to enable Cross and Dual Listings

- Reliance Industries trims stake in India’s Asian Paints

- S&P Global Ratings Expands Presence in India at GIFT City

- Private Credit Penetrates Asia-Pacific Securitization Markets

- Is IBC effective, or is it time for 2.0?

- Indian startups raise $184.75 million this week

- Distress Signals in FDI: Big Numbers Mask a Sharp Investor Exit

- Ankur Capital’s Subramanian on b2b focus, investment strategies, and more

- IKF Finance S Vasumathi Devi on IPO plans asset quality expansion goals and more

- Inside Japanese VC firm Enrission India Capital’s investment strategy in India

Job moves

- Bank of America Hires JPMorgan Executive to Lead India Equity Markets Unit

- Kunal Mehra boosts Phoenix Legal’s antitrust, M&A practices

- Lagna Panda boosts competition law talent at AP & Partners

- Oishika Dasgupta rejoins CAM, boosts capital markets team

- Rachika Sahay to boost CAM’s infrastructure practice

- Yes Bank Extends Prashant Kumar’s Term As CEO Amid Stake Sale Buzz, CEO Search Underway

- Honasa Consumer Appoints Ex-Flipkart, HUL Leader Yatish Bhargava as CBO

- Sun Pharma Elevates Kirti Ganorkar as MD; Shanghvi to Continue as Executive Chairman

- Anuradha Thakur to replace Ajay Seth on SEBI board

- RBC Capital Markets promotes two investment bankers to lead US advisory units

IPOs

- BIGBLOC subsidiary StarBigBloc gets shareholder approval to launch IPO, subject to regulatory nods and market conditions

- Adani eyes IPO of airport unit by 2027 speeds up $100b capex push

- The mix of adjectives and data reveals the real story in tech IPO documents

- Gujarat’s Fastest Growing Cafe Chain Tea Post Refiles IPO Papers

- Digitide Solutions lists at 58% premium, Bluespring Enterprises falls 44% on debut

- In second bid, Capillary to file IPO papers by October

Fundraising

- Snapmint set to raise $40 Mn led by General Atlantic

- D2C jewellery startup Giva to raise Rs 450 cr from Creaegis, others

- Indian SaaS startup MoEngage in talks with A91 Partners, others to raise funding

- India Digest: GIVA jewellery, Snapmint looking to raise funds

- Steptrade Capital announces first close of Rs 1,000 Cr SRF-II

- Shriram Group Launches Shriram Wealth, a strategic Joint Venture with Sanlam Group

- Garuda Aerospace Raises Additional $1M in Series B Round to Accelerate Drone Manufacturing and Global Expansion

- MakeMyTrip to raise $2.5 bn to slash Trip.com’s stake and voting power

- The Wealth Company launches ₹2,000 crore Bharat Bhoomi Fund to invest in real estate

- City Union Bank board approves ₹500 crore fundraising via QIP

- Advent making second attempt at Asia fund

- Chai Shots Nears $5M Round, Pehle Jaisa Secures $300K as Early-Stage Startups Attract Investor Attention

- Oben Electric Raises INR 50 Cr in Extended Series A

- Machaxi Raises $1.5M in Funding

- GEF Capital Partners eyes $600m fund after major success with Premier Energies

- Tata Consumer Products keeps its ‘antennas up’ for strategic acquisitions

- Sebi engages with venture capital funds directly to smoothen to transition AIFs

- Ex-Start-Up Execs Raise $101 Mn in 2024, Seed Funding Jumps 243%: Report

- InCred eyes second PE fund of up to ₹1,500 cr

- Advent plots dedicated APAC fund

- Tor, Nomura extend INR4.5bn private credit facility to Suruchi

- Nvidia, Samsung join SoftBank in robotics firm series B

- Avinya Ventures ropes in domestic LP for maiden VC fund

- Ethnicwear brand Kisah snags angel funding, plans larger Series A round

- Foo and KOKO restaurant owner preps new fundraise as growth appetite builds

- Physis Capital gets LP cheques from Haldiram’s Lotus herbals family offices

- Pontaq Ventures raises government backed capital for third fund

- Value Quest rolls out second private equity fund, marks first close

Compliance/regulatory update

- India’s central bank sends conflicting signals with surprise moves

- Jio Blackrock Secures SEBI Nod To Launch Investment Advisory Operations In India

- RBI Unlocks Flexibility For Foreign Owned And Controlled Indian Entities

- RBI May Resume Rate Cuts as Inflation Softens and Liquidity Needs Rise: Angel One

Harsh Batra

Harsh Batra